In Depth: 500 Years of Italian Master Drawings from the Princeton University Art Museum

This special exhibition focuses on the Museum’s renowned collection of more than one thousand Italian drawings—a valuable teaching and scholarly resource—which includes outstanding examples in a wide variety of styles and techniques, primarily by artists from the Renaissance and Baroque periods. The selected works, supplemented by two loans, capture the universal appeal of drawing as one of the most intimate manifestations of the creative process.

The Museum’s first exhibition devoted to this rich material since the late 1960s, 500 Years of Italian Master Drawings showcases approximately one hundred works from the fifteenth through twentieth centuries, with significant groups by Luca Cambiaso, Parmigianino, Guercino, Giambattista Tiepolo, and Amedeo Modigliani, as well as revelatory sheets by Vittore Carpaccio, Michelangelo, and Gianlorenzo Bernini. Also highlighted are works by less-celebrated masters who deserve to be better known, such as Marco Marchetti, Carlo Dolci, and Pasquale Ottino. Featuring rarely seen treasures, including an album of caricatures by Guercino once in the collection of Sir Joshua Reynolds, the exhibition celebrates the publication of a new scholarly catalogue that details more than two hundred works in the collection. The publication selectively revises and expands upon Felton Gibbons’s pioneering Catalogue of the Italian Drawings in the Art Museum, Princeton University (1977), bringing to fruition years of extensive object-based research, most recently supported by a generous grant from the Getty Foundation. While many of the works entered Princeton’s collection in the 1940s, almost half of the drawings chosen for the exhibition have either been acquired (through purchase, gift, or bequest) since the publication of Gibbons’s catalogue or have new attributions; a substantial number are being published and displayed for the first time. Many have been enriched by new discoveries (including several made through infrared reflectography) concerning technique, iconography, dating, function, and provenance, and a selection have been conserved in anticipation of the exhibition.

The Museum’s first exhibition devoted to this rich material since the late 1960s, 500 Years of Italian Master Drawings showcases approximately one hundred works from the fifteenth through twentieth centuries, with significant groups by Luca Cambiaso, Parmigianino, Guercino, Giambattista Tiepolo, and Amedeo Modigliani, as well as revelatory sheets by Vittore Carpaccio, Michelangelo, and Gianlorenzo Bernini. Also highlighted are works by less-celebrated masters who deserve to be better known, such as Marco Marchetti, Carlo Dolci, and Pasquale Ottino. Featuring rarely seen treasures, including an album of caricatures by Guercino once in the collection of Sir Joshua Reynolds, the exhibition celebrates the publication of a new scholarly catalogue that details more than two hundred works in the collection. The publication selectively revises and expands upon Felton Gibbons’s pioneering Catalogue of the Italian Drawings in the Art Museum, Princeton University (1977), bringing to fruition years of extensive object-based research, most recently supported by a generous grant from the Getty Foundation. While many of the works entered Princeton’s collection in the 1940s, almost half of the drawings chosen for the exhibition have either been acquired (through purchase, gift, or bequest) since the publication of Gibbons’s catalogue or have new attributions; a substantial number are being published and displayed for the first time. Many have been enriched by new discoveries (including several made through infrared reflectography) concerning technique, iconography, dating, function, and provenance, and a selection have been conserved in anticipation of the exhibition.

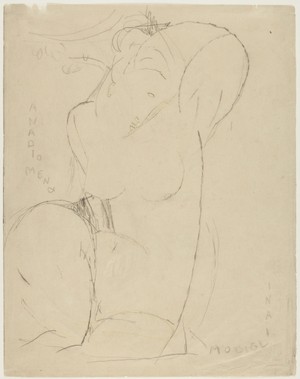

In the catalogue, the highlighted drawings are presented in chronological order, providing a capsule history of Italian art from the early Renaissance to early modernism. In contrast, the exhibition is organized along thematic lines, and it sets out to demonstrate the pivotal role played by disegno, or drawing, in the Italian design process, encompassing both the mental formulation and the physical act of creation—with a particular emphasis on drawings of the human figure. Whether made from life, recorded after sculptures, or born from the imagination, these evocations of the human body (usually male) are emblematic of the centrality of this object of scrutiny, idealization, and, ultimately, fragmentation within the history of Italian art. As charted in the publication, this trajectory is framed by the wiry self-controlled contours of Marcantonio Raimondi’s male nude (ca. 1505–9)—an inspired copy after Albrecht Dürer’s famous 1504 engraving of Adam and Eve—and the fractured, elliptical sinuosity of Modigliani’s female nude Anadiomena (ca. 1914–15). In the exhibition, Modigliani’s incisive graphite sketch appears in the introductory section dedicated to the diverse media and techniques employed by Italian artists, while Raimondi’s pen-and-ink drawing is found in a section titled “Drawing as Discipline” that explores the important role of copying in artistic education. Included in this section are examples by Giovanni Battista Naldini and Giandomenico Tiepolo after sculptures by Michelangelo and Alessandro Vittoria, demonstrating the path from derivation to originality.

In the catalogue, the highlighted drawings are presented in chronological order, providing a capsule history of Italian art from the early Renaissance to early modernism. In contrast, the exhibition is organized along thematic lines, and it sets out to demonstrate the pivotal role played by disegno, or drawing, in the Italian design process, encompassing both the mental formulation and the physical act of creation—with a particular emphasis on drawings of the human figure. Whether made from life, recorded after sculptures, or born from the imagination, these evocations of the human body (usually male) are emblematic of the centrality of this object of scrutiny, idealization, and, ultimately, fragmentation within the history of Italian art. As charted in the publication, this trajectory is framed by the wiry self-controlled contours of Marcantonio Raimondi’s male nude (ca. 1505–9)—an inspired copy after Albrecht Dürer’s famous 1504 engraving of Adam and Eve—and the fractured, elliptical sinuosity of Modigliani’s female nude Anadiomena (ca. 1914–15). In the exhibition, Modigliani’s incisive graphite sketch appears in the introductory section dedicated to the diverse media and techniques employed by Italian artists, while Raimondi’s pen-and-ink drawing is found in a section titled “Drawing as Discipline” that explores the important role of copying in artistic education. Included in this section are examples by Giovanni Battista Naldini and Giandomenico Tiepolo after sculptures by Michelangelo and Alessandro Vittoria, demonstrating the path from derivation to originality.

Embedded in the training of Italian artists by the middle of the fifteenth century, and subsequently academicized, disegno provided an enduring impetus for future generations to conceptualize a design and then realize that mental image on paper—the first mark-making step toward the project’s final realization on canvas or in stone. The exhibition’s organization by theme rather than by chronology is intended to engage the visitor with manifestations of the multivalent meanings of the term disegno, aptly described by Georges Didi-Huberman as “almost a floating signifier.” Disegno played a significant role, beginning in late fourteenth-century Florence, in elevating the status of painting, sculpture, and architecture from manual craft to liberal art—leading to the Florentine painter and art historian Giorgio Vasari’s assertion in the second edition of his Lives of the Artists (1568) that disegno was the father of all the arts.

Embedded in the training of Italian artists by the middle of the fifteenth century, and subsequently academicized, disegno provided an enduring impetus for future generations to conceptualize a design and then realize that mental image on paper—the first mark-making step toward the project’s final realization on canvas or in stone. The exhibition’s organization by theme rather than by chronology is intended to engage the visitor with manifestations of the multivalent meanings of the term disegno, aptly described by Georges Didi-Huberman as “almost a floating signifier.” Disegno played a significant role, beginning in late fourteenth-century Florence, in elevating the status of painting, sculpture, and architecture from manual craft to liberal art—leading to the Florentine painter and art historian Giorgio Vasari’s assertion in the second edition of his Lives of the Artists (1568) that disegno was the father of all the arts.

Seeking to contextualize several key drawings, the exhibition is punctuated by a dozen works in other media—sculptures, paintings, prints, and a book—from the Museum’s collection as well as from Firestone Library, that broaden and deepen the viewer’s understanding of drawing’s role in the artistic process. One such example is the juxtaposition of Vittorio Carpaccio’s luminous drawing of two women— one in Mamluk dress—with the source of his appropriation, a woodcut illustration from a popular late fifteenth-century travel narrative about a pilgrimage to the Holy Land. By displaying the book and Carpaccio’s drawing side by side, we can envision Carpaccio sketching from the book and transforming his source before incorporating the two women into one of his most celebrated paintings, the Triumph of Saint George (1501–8). The subject of that work—the conversion of an Islamic ruler to Christianity—exemplifies the tension between East and West that is fundamental to an understanding of Venetian Renaissance art and culture.

The drawing and the book will be included in the section “Stages of Design,” which takes the viewer through the different steps of the design process. By the early sixteenth century this process had been codified, beginning with rapid brainstorming sketches (called schizzi, and subsequently primi pensieri, or first thoughts), followed by studies of individual figures (or studi), and culminating with finished drawings (or modelli), which were then transferred to a full-scale cartoon (cartone). Among the numerous examples of figure studies in “Stages of Design” is Jacopo Tintoretto’s combustible male nude, preparatory for a muscular angel in his Resurrection in the Scuola di San Rocco, Venice (1578–81) and probably based on a wax or clay figurine. Beyond its functional identity, the drawing also provides the perfect aesthetic and theoretical companion to the contemporary red-chalk study of a seated male model, made from life, by the lesser-known Florentine Mannerist Girolamo Macchietti. When seen together in the exhibition, the two chalk drawings provide a textbook contrast between the Venetian emphasis on painterly effects, or colorito (translated to broken contours and smudged shading), and the Florentine predilection for the linear qualities of disegno (as expressed in long continuous contours and precise modeling). Both squared for transfer, these fully realized figure drawings would have been preceded by preliminary pen and- ink sketches, such as Jacopo Zucchi’s flurried and cryptic draft for an unidentified Medici commission. The exploratory impetus behind this quintessential manifestation of Mannerist elegance can also be found in a host of later examples related to specific projects, ranging from Annibale Carracci’s harsh scribble of a concept for one of his signature works, Choice of Hercules, to Modigliani’s sketches on inexpensive graph paper for one of his iconic Head sculptures.

The drawing and the book will be included in the section “Stages of Design,” which takes the viewer through the different steps of the design process. By the early sixteenth century this process had been codified, beginning with rapid brainstorming sketches (called schizzi, and subsequently primi pensieri, or first thoughts), followed by studies of individual figures (or studi), and culminating with finished drawings (or modelli), which were then transferred to a full-scale cartoon (cartone). Among the numerous examples of figure studies in “Stages of Design” is Jacopo Tintoretto’s combustible male nude, preparatory for a muscular angel in his Resurrection in the Scuola di San Rocco, Venice (1578–81) and probably based on a wax or clay figurine. Beyond its functional identity, the drawing also provides the perfect aesthetic and theoretical companion to the contemporary red-chalk study of a seated male model, made from life, by the lesser-known Florentine Mannerist Girolamo Macchietti. When seen together in the exhibition, the two chalk drawings provide a textbook contrast between the Venetian emphasis on painterly effects, or colorito (translated to broken contours and smudged shading), and the Florentine predilection for the linear qualities of disegno (as expressed in long continuous contours and precise modeling). Both squared for transfer, these fully realized figure drawings would have been preceded by preliminary pen and- ink sketches, such as Jacopo Zucchi’s flurried and cryptic draft for an unidentified Medici commission. The exploratory impetus behind this quintessential manifestation of Mannerist elegance can also be found in a host of later examples related to specific projects, ranging from Annibale Carracci’s harsh scribble of a concept for one of his signature works, Choice of Hercules, to Modigliani’s sketches on inexpensive graph paper for one of his iconic Head sculptures.

Complementing “Stages of Design” is “Autonomy of Expression,” a wide-ranging display of drawings made beyond the confines of commissions that illustrates the growing status of drawing as an autonomous and collectible work of art, exemplified by mythological and historical settings, landscapes, and genre scenes. This includes an enigmatic interior with two men playing a racket game, attributed to Giulio Benso. Also included is a dazzling array of caricatures by Guercino and Giovanni Battista Tiepolo—artists whose virtuoso draftsmanship is examined in more detail, together with examples by Luca Cambiaso, in “A Closer Look: Masters of Disegno.” This section pays homage to the Museum’s rich holdings of works by these artists—made possible largely thanks to Dan Fellows Platt, Class of 1895. Platt and former Museum director Frank Jewett Mather Jr. represent the two cornerstones of the Italian drawings collection at Princeton. Their place in the history of collecting and connoisseurship of Italian drawings is briefly explored in the exhibition’s final section, “Lasting Legacies, Changing Identities,” which casts its lens on a group of exquisite drawings by the Mannerist master Parmigianino. One of these had been given to the Museum by Mather and was classified as a derivative work until recent scholarship demonstrated its authenticity.

Both Princeton collectors sought drawings that could at once provide teachable moments and transformative experiences. While their scholarly passion for Italian drawings did not stray far from the object itself, subsequent research on this critical component of the Museum’s collection has incorporated traditional connoisseurship into a broader spectrum of material and contextual issues, thereby expanding the art-historical significance of these drawings and at the same time celebrating their essential vitality and universal appeal.

Laura M. Giles

Heather and Paul G. Haaga Jr., Class of 1970, Curator of Prints and Drawings

500 Years of Italian Master Drawings from the Princeton University Art Museum has been made possible by generous support from Diane W. Burke; Susan and John Diekman, Class of 1965; John H. Rassweiler; the Allen R. Adler, Class of 1967, Exhibitions Fund; The Peter Jay Sharp Foundation; the Caroline G. Mather Fund; the Apparatus Fund; and the New Jersey State Council on the Arts/Department of State, a Partner Agency of the National Endowment for the Arts. The publication has been made possible, in part, by the Barr Ferree Foundation Publication Fund, Princeton University; and the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, with the assistance of The Getty Foundation. Further support has been provided by the Partners and Friends of the Princeton University Art Museum.