Celebrating Fifty Years of Photography at Princeton

The hiring of a new faculty member does not typically merit national newspaper coverage, but Princeton’s announcement in 1972 that Peter Bunnell would be joining the University from the Museum of Modern Art as the inaugural David Hunter McAlpin Professor of the History of Photography and Modern Art made headlines. Princeton’s new “Photo Arts Chair,” as the New York Times dubbed the position, was the country’s first endowed professorship of photography at a time when the discipline was only beginning to be accepted as a serious academic pursuit and photographs were not widely collected by museums—and thus it was news. Until that point, studying the history and aesthetics of picture taking required determination.

The hiring of a new faculty member does not typically merit national newspaper coverage, but Princeton’s announcement in 1972 that Peter Bunnell would be joining the University from the Museum of Modern Art as the inaugural David Hunter McAlpin Professor of the History of Photography and Modern Art made headlines. Princeton’s new “Photo Arts Chair,” as the New York Times dubbed the position, was the country’s first endowed professorship of photography at a time when the discipline was only beginning to be accepted as a serious academic pursuit and photographs were not widely collected by museums—and thus it was news. Until that point, studying the history and aesthetics of picture taking required determination.

Art history textbooks of the era typically omitted photography, and the Library of Congress classified it as a craft rather than a fine art. Bunnell, the first Yale student to attempt a dissertation on a photographer, described for the New York Times the tenacity needed to pursue the subject in the 1960s: “ Despite a growing awareness of still photography’s importance, there was no program where you could study its aesthetics and history. You had to pick your way through a variety of academic programs, and if you were lucky, the Fine Arts faculty would graciously give you permission to concentrate on photography.”

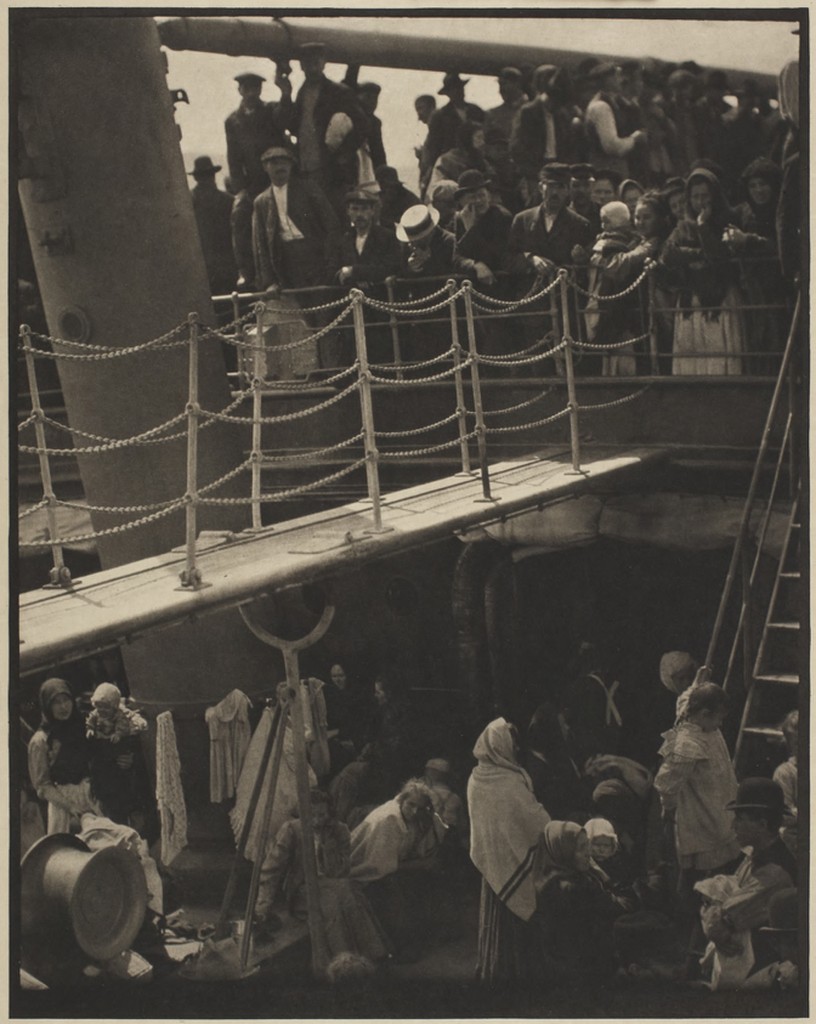

Although nearly 150 years had passed since its invention, the camera’s supposed objectivity and its primacy in advertising prevented many art historians and curators from considering photography a serious collecting area. Photography collections were often an afterthought in museums, typically acquired as donations rather than as purchases. The Princeton University Art Museum received its first photograph, The Steerage (1907) by Alfred Stieglitz, in 1949 as a gift from former Museum director Frank Jewett Mather. At that time the Museum of Modern Art was an outlier with a stand-alone department of photography founded in 1940, following the success of its landmark survey exhibition Photography 1839–1937. In comparison, the Metropolitan Museum of Art established its photography department only in 1992, and many university art museums began actively collecting photographs in the 1970s.

Although nearly 150 years had passed since its invention, the camera’s supposed objectivity and its primacy in advertising prevented many art historians and curators from considering photography a serious collecting area. Photography collections were often an afterthought in museums, typically acquired as donations rather than as purchases. The Princeton University Art Museum received its first photograph, The Steerage (1907) by Alfred Stieglitz, in 1949 as a gift from former Museum director Frank Jewett Mather. At that time the Museum of Modern Art was an outlier with a stand-alone department of photography founded in 1940, following the success of its landmark survey exhibition Photography 1839–1937. In comparison, the Metropolitan Museum of Art established its photography department only in 1992, and many university art museums began actively collecting photographs in the 1970s.

It is therefore no surprise that the advent of Princeton’s dedicated professorship of photography was seen as a newsworthy development. Wen Fong, then chair of Princeton’s Department of Art and Archaeology, stated in a press release that the new McAlpin Professorship was a “significant departure for our department and the study of the history of art in general” but also a welcome innovation for the second-oldest department in the country, which had “ played an important role in turning the study of art into a serious academic discipline.” The University had long been on the leading edge of the field, an early adopter in 1882 of a discipline that was in the nineteenth century mainly practiced at major European universities, particularly in Germany. In the years surrounding World War I, Princeton was the leading center for the study of medieval art in the nation if not the world. Beginning in the 1950s, Princeton’s pioneering faculty, led by Fong, helped to shape the field of East Asian art history. However, it took the extraordinary vision and generosity of former Princeton University trustee David H. McAlpin, Class of 1920 (1897–1989), to make Princeton a pioneer in the history of photography.

An investment banker and philanthropist, McAlpin became a passionate collector of photographs beginning in the 1930s, when personal photography collections were exceedingly rare. As a trustee of the Museum of Modern Art, he headed the committee that organized its first department of photography. McAlpin had long hoped to establish his alma mater as a center for photographic study, offering donations for that purpose as early as the 1960s that were initially rebuffed. In 1967, he founded an annual photography lecture series in memory of Alfred Stieglitz, and in 1971, he and his wife, Sarah “Sally” Sage McAlpin, made a foundational donation to the Museum of nearly five hundred photographs—the remainder of their collection—by mostly American innovators of the medium, including Ansel Adams, Imogen Cunningham, Alfred Stieglitz, Paul Strand, Edward Weston, and Minor White.

An investment banker and philanthropist, McAlpin became a passionate collector of photographs beginning in the 1930s, when personal photography collections were exceedingly rare. As a trustee of the Museum of Modern Art, he headed the committee that organized its first department of photography. McAlpin had long hoped to establish his alma mater as a center for photographic study, offering donations for that purpose as early as the 1960s that were initially rebuffed. In 1967, he founded an annual photography lecture series in memory of Alfred Stieglitz, and in 1971, he and his wife, Sarah “Sally” Sage McAlpin, made a foundational donation to the Museum of nearly five hundred photographs—the remainder of their collection—by mostly American innovators of the medium, including Ansel Adams, Imogen Cunningham, Alfred Stieglitz, Paul Strand, Edward Weston, and Minor White.

The McAlpin gift of photographs was transformational. Museum director Patrick Kelleher highlighted how these works elevated Princeton as a leader in a burgeoning discipline in a letter to McAlpin: “Dear, dear David: What a major breakthrough you have made single-handedly, for The Art Museum in that princely gift of your collection . . .dealing with the art of American photography. In one fell swoop the Museum can now begin to compete with the best in an entirely new field only sparsely represented previously in the collections.” A year later, a $1 million gift from the couple created the David Hunter McAlpin Professorship of the History of Photography and Modern Art.

The flourishing of photography at Princeton was due as much to McAlpin’s foresight as it was to the dedication of the first McAlpin Professor, Peter Bunnell (1937–2021), who also served as the Museum’s curator of photography and later its director. Upon his appointment to Princeton, Bunnell wrote, “With this program we hope to establish a major center where the serious student and scholar may undertake intensive studies, and eventually we hope to provide for universities and museums elsewhere the necessary staff to develop a new depth in the study of photography.” Bunnell amply fulfilled that promise: Many of his undergraduate and graduate students followed him into the field, making their mark as professors, curators, photographers, and collectors. It is impossible to overstate Bunnell’s impact on the field, recognized when in 2011 a group of his former students collectively endowed the Museum’s curatorship in photography in his name, a position now held by Katherine Bussard.

The flourishing of photography at Princeton was due as much to McAlpin’s foresight as it was to the dedication of the first McAlpin Professor, Peter Bunnell (1937–2021), who also served as the Museum’s curator of photography and later its director. Upon his appointment to Princeton, Bunnell wrote, “With this program we hope to establish a major center where the serious student and scholar may undertake intensive studies, and eventually we hope to provide for universities and museums elsewhere the necessary staff to develop a new depth in the study of photography.” Bunnell amply fulfilled that promise: Many of his undergraduate and graduate students followed him into the field, making their mark as professors, curators, photographers, and collectors. It is impossible to overstate Bunnell’s impact on the field, recognized when in 2011 a group of his former students collectively endowed the Museum’s curatorship in photography in his name, a position now held by Katherine Bussard.

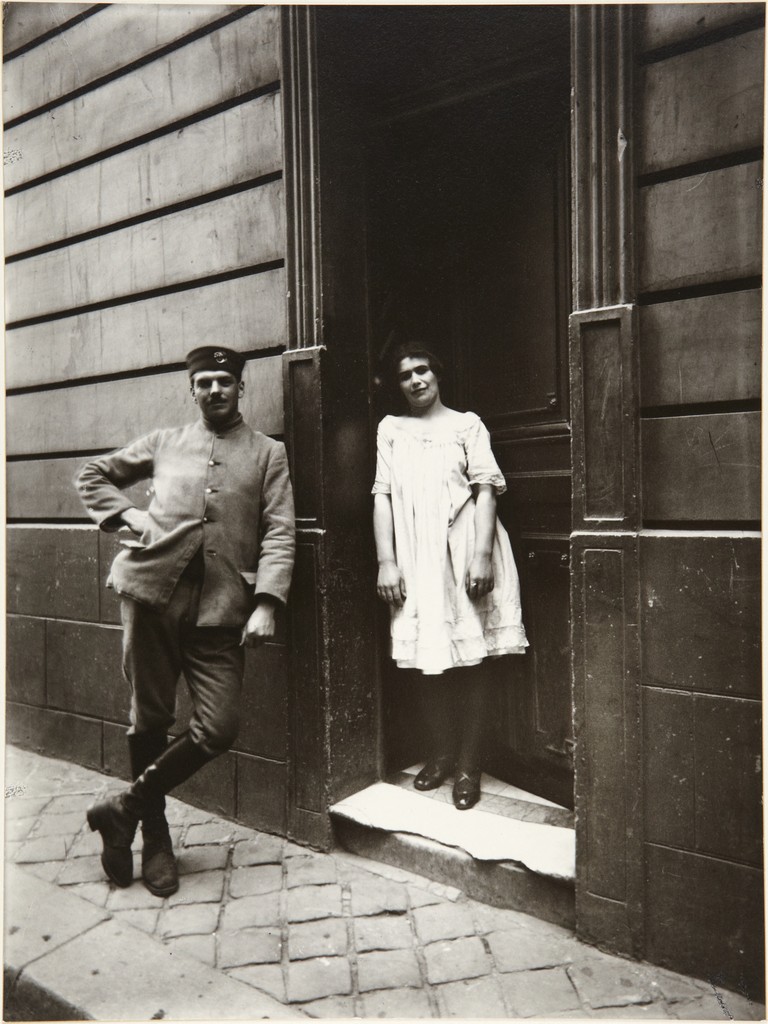

At the heart of Bunnell’s vision for photography at Princeton was the integration of the Museum’s collections with teaching, a relationship he described as being “as basic as a laboratory to the student of biology or chemistry.” Bunnell was renowned for his hands-on courses, in which students closely examined and even handled original works of art. In a 1998 New York Times profile, he said of his classes, “I teach all the discussion sections of my courses with only original photographs, no slides. To be able to demonstrate what it is that makes [the French photographer Eugène] Atget so remarkable, a reproduction won’t do.”

At the heart of Bunnell’s vision for photography at Princeton was the integration of the Museum’s collections with teaching, a relationship he described as being “as basic as a laboratory to the student of biology or chemistry.” Bunnell was renowned for his hands-on courses, in which students closely examined and even handled original works of art. In a 1998 New York Times profile, he said of his classes, “I teach all the discussion sections of my courses with only original photographs, no slides. To be able to demonstrate what it is that makes [the French photographer Eugène] Atget so remarkable, a reproduction won’t do.”

The legacy of Bunnell’s object-based teaching continues today. In a typical year, the Museum’s staff pull one thousand photographs from the collections for classroom use. Anne McCauley, who succeeded Bunnell as the McAlpin Professor, has remained an advocate for teaching from original works, regularly holding courses in the Museum’s galleries and object study classrooms, as well as continuing Bunnell’s practice of faculty curation of major exhibitions, including the landmark 2017 exhibition Clarence H. White and His World: The Art and Craft of Photography, 1895–1925.

The Museum’s photography holdings have grown to include more than 43,000 works of art, including the photographic archives of the artists Ruth Bernhard, Clarence H. White, and Minor White (no relation). Over the years, each successive curator of photography has focused on acquiring works that further the faculty’s teaching and research needs. Bunnell pioneered the collecting of Japanese photography, while successors like Joel Smith—himself a former Bunnell student—led the field in collecting vernacular photos, and Bussard has invested vigorously in photojournalism, works by women photographers, and photographs grappling with the legacies of enslavement.

The Museum’s photography holdings have grown to include more than 43,000 works of art, including the photographic archives of the artists Ruth Bernhard, Clarence H. White, and Minor White (no relation). Over the years, each successive curator of photography has focused on acquiring works that further the faculty’s teaching and research needs. Bunnell pioneered the collecting of Japanese photography, while successors like Joel Smith—himself a former Bunnell student—led the field in collecting vernacular photos, and Bussard has invested vigorously in photojournalism, works by women photographers, and photographs grappling with the legacies of enslavement.

Set to open in late 2024, the new home for the Princeton University Art Museum will afford fresh opportunities to present the Museum’s collections of photography—including time-based media—to new generations of students and other visitors. Museum director James Steward notes, “The visionary gift McAlpin made fifty years ago ensured that Princeton would become a pioneer in the study of photography; that legacy is now in our DNA and will remain at the heart of our work for decades to come.”

Christine Minerva

Writing and Communications Assistant