Highlights from the Gillett G. Griffin Bequest

Gillett G. Griffin, curator of Pre-Columbian and Native American art, emeritus, bequeathed more than 3,500 works of art to the Princeton University Art Museum in 2016. More than 2,400 are ancient American objects, which compose the majority of Princeton’s renowned collections in this area. The remaining works in the bequest span the globe and time, ranging from works of Asian and African art to works on paper—and include stone tools made by very early humans, which extend the chronological scope of the Museum’s holdings by tens of thousands of years. On the second anniversary of his death, his presence is still felt warmly and indelibly within the Museum. This story illustrates the breadth of this extraordinary gift, as well as Gillett’s keen aesthetic eye, through an in-depth look at works from several areas of the collection.

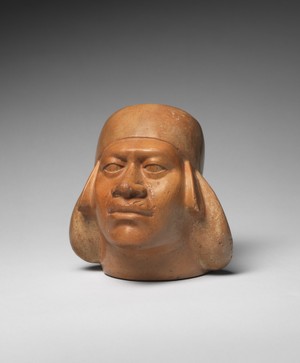

The vividly realistic features and expression of this mold-made Moche vessel are startling. Created as jars or bottles, so-called portrait vessels reached an unprecedented level of naturalism, culminating among the Mochica along the north coast of Peru between A.D. 500 and 800. They depict what many scholars have argued were specific individuals. Researchers have named figures such as this example "Cut Lip" because of the distinctive scar at the left portion of his upper lip. His purported portrait occurs on numerous vessels, apparently at various stages of life from boyhood through his mid-thirties. More recently, however, other specialists have noted subtle variations in the form and location of scars on "Cut Lip" portraits, leading them to promote the alternative interpretation that such marks reflect a practice of ritual scarification. Instead of depicting specific historical individuals, then, such "portrait heads" may instead represent idealized types, indicating social rank, specialization, or ethnicity.

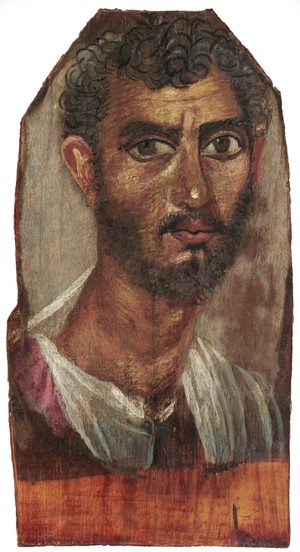

Among several works of Egyptian art in the Griffin bequest is a Faiyum portrait, named for a region on the west bank of the Nile, south of Cairo. The portrait of a bearded young man is painted on a wooden board in the encaustic technique, using wax as a binder. The board originally was placed over the face of a mummified corpse, secured by linen wrappings. The practice of affixing a lifelike image of the deceased to a mummy coffin or cartonnage was one of many Egyptian traditions adopted by the Romans when they added Egypt to their empire. Such images were thought to help preserve the souls of the dead but also functioned as memorials, since there is evidence that mummies so equipped were installed for periods in the courtyards of private homes. They have been found in great numbers in the Faiyum and at sites farther south, such as Antinoöpolis, the city founded by the emperor Hadrian after his favorite, Antinous, drowned in the Nile. Comparison with sculpted portraits suggests that the Museum’s painting dates to the mid-second century. Although the youth's features have an individual character, his image may not be a realistic portrait. The youth's dark skin and curly hair hint at the multiethnic composition of Roman Egypt. In the great metropolis of Alexandria, Romans mixed with Greeks, Jews, and native Egyptians to form a cosmopolitan society with its own distinctive blend of cultural traditions.

Between 1400 and about 1908, Akan goldsmiths cast some three million brass weights (mrammuo, singular abrammuo) to measure the locally sourced currency of gold dust. An easily divisible substance that promoted regional trade, gold also held symbolic power as the embodiment of kra (life force) and as the representation of the sun’s earthly partner. As artistic skill increased, weights produced from the seventeenth century through the end of the nineteenth century incorporated imagery of people, animals, plants, and objects. Like most Akan art, the visual forms of gold-weights were closely linked to the verbal art of proverbs (mmε, singular εbε), widely known truth maxims about Akan culture and values. This gold-weight, cast from imported brass using the lost-wax method, is in the form of identical birds seated on a stepped rectangular platform. The birds face the same direction, their egg-shaped bodies in contrast to their flat trapezoid-shaped tails. The crest and wings are composed of concentric half-circles, and their thin, curving necks add a sense of movement and inquisitiveness.

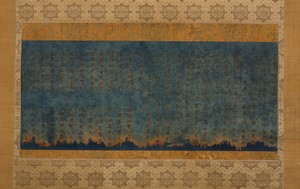

Damaged by a fire, this fragment is a part of the Flower Garland Sutra (Kegonkyō or Avatamsaka sutra), one of the most prominent East Asian Buddhist sutras. The segment comes from a long manuscript that was burned in a fire at Nigatsudō Hall, a structure in the Tōdaiji temple complex in Nara, Japan, in 1667—hence the name "burned sutra." The sutra was originally made around 744, during the Nara period, when Buddhism was established as a significant religion throughout the country. Temples therefore had a need for Buddhist texts; at Tōdaiji alone, the imperial family employed over 250 high-ranking scribes who used expensive and elaborate techniques to copy the most important Buddhist texts. The skilled craftsmanship is evident in the scroll, with the use of precious materials for the text itself and also for the surrounding mount, decorated with golden floral motifs and the dharmachakra, or the wheel of the Noble Eightfold Path. Conversely, the singed edges on the delicate paper show the other side of Buddhism—the impermanence of life (anicca), one of the Four Noble Truths. That is to say, everything, including these luxurious handscrolls, is temporary.

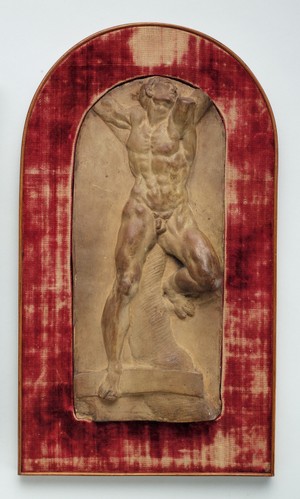

The Death of Haman was painted by Michelangelo on one of the four pendentives of the Sistine Chapel representing scenes of the salvation of the Jewish people (the others are Judith and Holofernes, David and Goliath, and the Brazen Serpent). The twisting and extended body of Haman--hanged on a gallows in the Bible but attached to a cross in Michelangelo’s interpretation—was of interest to young artists visiting Rome, many of whom drew after it. This sketch in relief may have been made as a study device. It might also have been one among similar sketches of other famous works, made to serve the same function as prints or drawings in the era before photography, to provide a stock of motifs that could be consulted throughout the artist’s career. The author of this sketch, his nationality, and his century have not been identified, but it is a fine example of this type of academic sketch.