Last Look | History on View in the Gallery of American Art

![Dorothea Lange, American, 1895–1965: Ten cars of evacuees of Japanese ancestry are now aboard and the doors are closed. Evacuees are bound for Merced Assembly Center [Temporary Detention Center], California, 1942, printed ca. 1955–65. Gelatin silver print. Museum purchase, Kathleen Compton Sherred Fund for Acquisitions in American Art (2018-28). Photograph by Dorothea Lange titled Ten cars of evacuees of Japanese ancestry are now aboard and the doors are closed. Evacuees are bound for Merced Assembly Center [Temporary Detention Center], California, 1942, printed ca. 1955–65.](https://puam-loris.aws.princeton.edu/loris/PUAMSTU2018-1931010.jp2/full/300,/0/default.jpg)

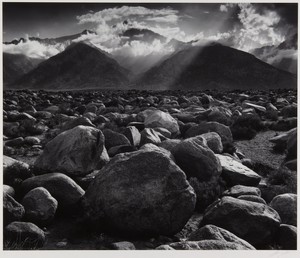

Don’t miss your chance to see two outstanding photographs–by Dorthea Lange and Ansel Adams–in the gallery of American art. The photographs will be on view through mid-September.

Don’t miss your chance to see two outstanding photographs–by Dorthea Lange and Ansel Adams–in the gallery of American art. The photographs will be on view through mid-September.

Following the Japanese attack on the United States in 1941, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, which led to the incarceration of more than 110,000 Japanese citizens and legal residents of Japanese ancestry. Working for the War Relocation Authority (WRA), Lange was one of the photographers who documented the forced removals. She sought to expose the racial biases of a policy that forced US citizens to leave their homes and communities for the duration of the war.

On November 12, 1943, Lange wrote to Adams:

"I fear the intolerance and prejudice is constantly growing. We have a disease. It's Jap-baiting and hatred. You have a job on your hands to do to make a dent in it—but I don't know a more challenging nor more important one. I went through an experience I'll never forget when I was working on it and learned a lot, even if I accomplished nothing."

With these words of encouragement and concern from Lange, Adams undertook an independent project photographing the Manzanar Internment Camp, one of the detention centers where Japanese Americans were confined without being charged with a crime or given due process.

Hung together, Lange’s portrait, a recent acquisition, and an Adams landscape long held in the collection present this historical period through two distinctly different representations, each amplifying the other. Lange’s photograph captures the emotions of a Japanese American woman being taken to the Merced Temporary Detention Center. The imposing view of Mount Williamson in Adams’s photograph alludes to the hardship that characterized the incarceration camp but attempts to describe the relationship between the detainees and the landscape beyond the camp, here illuminated by the crepuscular rays (often called "god rays") to suggest a higher power. Lange’s depiction of uprootedness in the gesture of a single person contrasts with and complements Adams’s charged sense of place.

Hung together, Lange’s portrait, a recent acquisition, and an Adams landscape long held in the collection present this historical period through two distinctly different representations, each amplifying the other. Lange’s photograph captures the emotions of a Japanese American woman being taken to the Merced Temporary Detention Center. The imposing view of Mount Williamson in Adams’s photograph alludes to the hardship that characterized the incarceration camp but attempts to describe the relationship between the detainees and the landscape beyond the camp, here illuminated by the crepuscular rays (often called "god rays") to suggest a higher power. Lange’s depiction of uprootedness in the gesture of a single person contrasts with and complements Adams’s charged sense of place.