Lawrence Lek's Virtual Worlds

What might it mean to host, to engage with, and to be an artist “in residence” at a time when international travel is restricted and gatherings are taking place in virtual spaces?

The above question describes not only the logistical challenge that faced preparations for the Sarah Lee Elson, Class of 1984, International Artist-in-Residence program this past year. The very idea of a residency, much like the nature of a campus community, took on a different character in 2020, requiring expansive thinking and new modes of convening. Students began to attend classes via Zoom videoconferences, and art experiences—the final studio critique for an art major or a tour of the Museum’s galleries—were accessible only as a series of video shorts embedded in a website. The past months have underscored challenging questions about how digital technologies are altering individual identities, community organizing, international relations, structures of belief, and cultural traditions. Such considerations led us to the multimedia digital artist, filmmaker, and musician Lawrence Lek, whose work likewise engages the ways in which digital technologies transform daily life—modes of both labor and leisure—and increasingly call into question the role of the human in a machine-driven society.

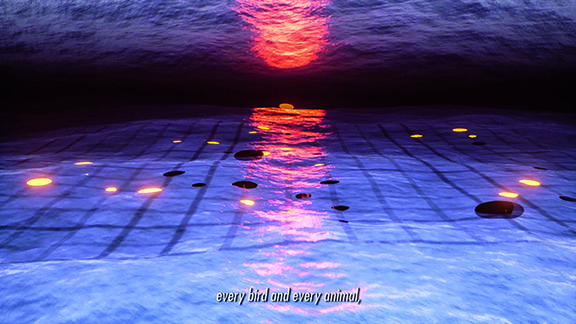

In a corpus of work that includes virtual-reality experiences, films, interactive games, musical albums, and digital essays, Lek mines the dynamic tension between systems of artificial intelligence and human subjectivity. His 2017 high-definition video and sound installation Geomancer presents a coming-of-age story—the narrative genre of individual becoming—as experienced by an entity of artificial intelligence, the film’s protagonist, Geomancer. The film follows Geomancer’s arrival on Earth, where she confronts the structures of human civilization. Taking the form of an anthropomorphized satellite, she opens the film with a series of existential ponderings:

Do you know what it is to see every wave, every bird, and every animal, a trillion shards of sunlight reflected on the water? . . . And, not just to see, but to remember everything with every detail etched into a neural network? Total recall, forever.

By setting up a series of rhetorical questions, Lek structures the film as an exploration of how both the possibilities and the limitations of computerized learning reveal the quintessential traits of humanity. As befits the coming-of-age genre, this is all an interior monologue, and Geomancer’s self-reflective answers reveal the price of this digital omniscience:

If I had hands, I would be a sculptor. If I had a voice, I would sing. If I had a soul, I would pray.

Creativity, individual expression, faith, fear, exhaustion, forgetfulness, and mortality are the terrain of the human, and while some of these traits are commonly perceived as weaknesses, here they are simultaneously strategies for survival and sources of innovative possibility. Such revelations are a through line in Lek’s work, which considers the growth, application, and dissemination of digital media as lenses that have magnified social patterns and altered our views on the definition of the individual and the formation of shared cultural values.

Lek developed Geomancer following an investigation into the historical, cultural, commercial, and international construction of Chinese identity as it is expressed and circulated online. That research coalesced into Sinofuturism (1839–2046 AD), a 2016 video essay structured as a cultural treatise. Sinofuturism offers a theory of the seven key stereotypes that define Chinese society internally as well as from international perspectives. Through a montage of found imagery, video clips, and news reports in multiple languages, Lek explores the roots of these stereotypes, which emerge from the confluence of cultural traditions, external biases, economic pressures, and efforts to mediate the human responses to computerized systems of production and socialization. He considers forms of automated thinking—replication, repetition, and mastery—embedded in historical forms of education or artistic practice in China as well as how these practices translate to modes of communal entertainment—gaming, gambling, and sport—as an economy of industrial production operated by humans becomes a system of automated production lines operated by robots and computers. How then, Sinofuturism posits, do we understand the space between the human and the machine, between artificial intelligence and culture?

As a Malaysian Chinese artist born in Frankfurt, Germany, raised in Singapore, and currently based in London, where he is pursuing a PhD in machine learning at the Royal College of Art, Lek is especially well positioned to consider cultural and national identity as a multivalent experience. It is in this position of intermediacy, balanced between perspectives—whether AI versus human, British versus Malaysian Chinese, or grounded in the historical specificities of Singapore versus imagined in a virtual future—that one might realize the most empathic response to the distanced realities and digitally mediated experiences of our present moment. Thanks to and as part of the Elson International Artist-in-Residence program, both Geomancer and Sinofuturism (1839–2046 AD) will become part of the Museum’s collections.

Mitra Abbaspour

Haskell Curator of Modern and Contemporary Art