Student Voices | Guerrilla Girls

What responsibility do museums, art collectors, critics, and curators have to historically underrepresented artists, in particular women and people of color? This is the central question that the Guerrilla Girls answer in their prolific series of posters, billboards, bus advertisements, magazine spreads, books, letter writing campaigns, and protest actions.

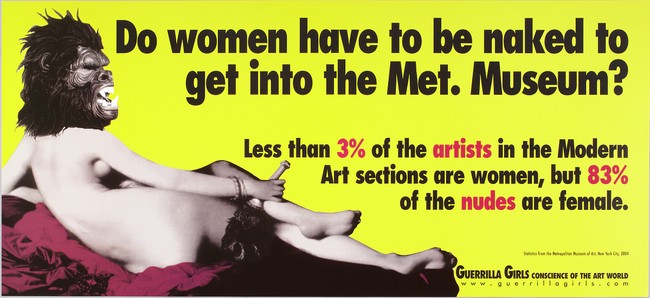

This essay highlights 3 of the 103 works created by the Guerrilla Girls that are held in the Princeton University Art Museum’s collections, and it considers the ways in which this influential group has approached the question of responsibility and accessibility to the art world using humor, statistics, and politically motivated, explicitly feminist rhetoric. A self-described group of feminist activist artists, the Guerrilla Girls began operating in 1985, with a series of posters plastered all over the streets of SoHo and the East Village in New York City, in response to the 1984 exhibition titled International Survey of Painting and Sculpture at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, in which less than ten percent of the 169 chosen artists were women. The members of the Guerrilla Girls remain anonymous by wearing gorilla masks and working under pseudonyms, taking on the names of dead women artists. The anonymity of the members serves several purposes, including protecting their identities and their own artistic careers, as well as placing the focus on their message rather than on the individuals producing that message. (They were inspired to wear gorilla masks after an early meeting in which one member accidentally misspelled “Guerrilla” as “Gorilla.”) Borrowing the names of dead women artists also allows the Guerrilla Girls to recognize and reinforce the place of these women in art history.

Since 1985, their numbers have grown, and they continue to produce new work, addressing, for instance, police violence and voting rights in 2020. Although they often disagree among themselves on whether their work should be considered art or simply activism, they have been featured in many museums and exhibitions since their origins.

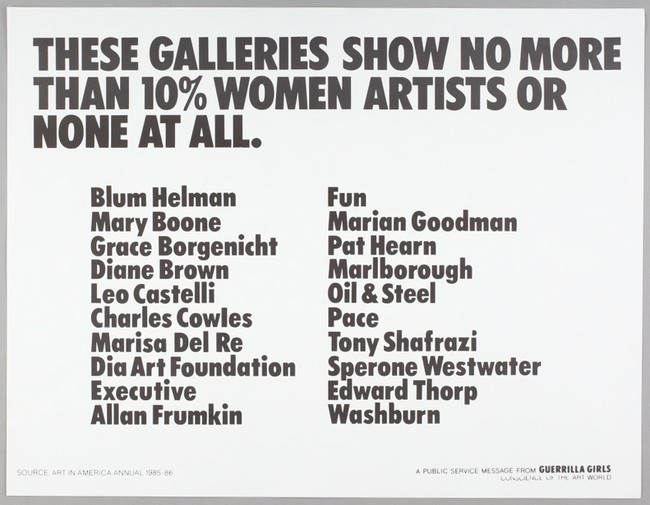

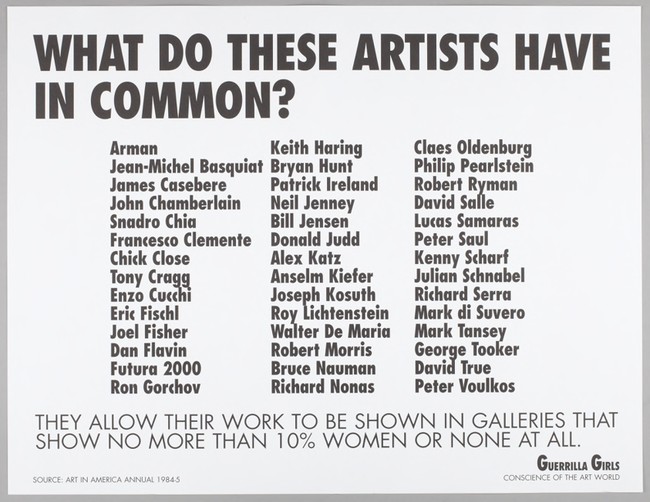

The two posters that launched the Guerrilla Girls’ long career of publicly drawing attention to discrimination and prejudice in the art world,These Galleries Show No More Than 10% Women Artists or None at All and What Do These Artists Have in Common?, were visually simple broadsheets with a powerful message. These Galleries Show No More Than 10% Women Artists or None at All states its title in bold capital letters followed by two columns of gallery names. In the bottom right corner, in smaller text, the work is tagged with the line “A public service message from Guerrilla Girls conscience of the art world.” The black-and-white poster, simple sans serif font, and capital letters allow the work to present the facts in a bold, honest, and unmistakable way. The no-nonsense appearance of this work places all of the emphasis and attention on the galleries in question and accomplishes a goal the Guerrilla Girls often stated as their motivation: exposing gender and racial biases and embarrassing those responsible into doing something about it.

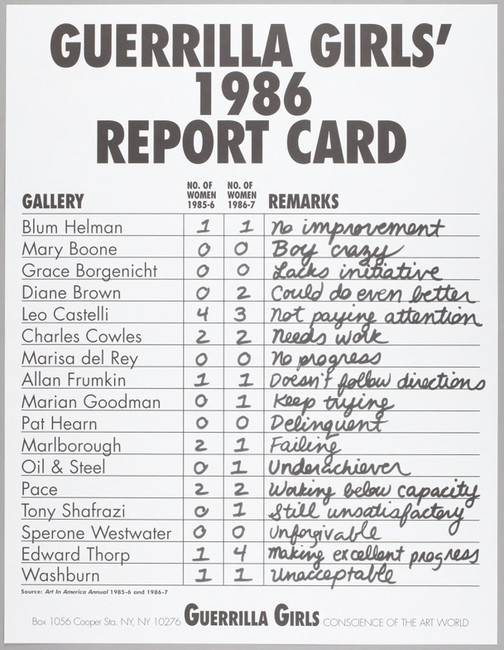

Guerrilla Girls’ 1986 Report Card takes this embarrassment a step further by combining gallery statistics with a sharply humorous commentary on the progress—or lack thereof—of many of the same galleries they called out in their earliest posters. This work takes the form of a grade-school report card with four columns: gallery, number of women artists shown at that gallery in 1985–86, number of women artists shown at that gallery in 1986–87, and remarks. Feminine, curly handwriting gives sharp comments for the galleries with no improvement or a dip in numbers—including remarks such as “boy crazy,” “lacks initiative,” and “doesn’t follow directions.” The work is once again tagged at the bottom with “Guerrilla Girls conscience of the art world.” The curly handwriting, like the use of “Girls” in the group’s name, reclaims and insists on a feminine voice in a field largely dominated by male voices. The repurposed format of the report card directly addresses the issue of the galleries’ failure to learn their lesson, using the same type of language typically found on the report cards of young girls, seeking to regulate their behavior. The humor in the piece generates interest while making the statistics more approachable, publicly reproaching some of the institutions guilty of underrepresentation.

The pieces presented in this online collection represent only a small subsection of a much larger body of work. While the Guerrilla Girls primarily targeted issues of representation within the art world, they also took on other political issues, including abortion rights, the Gulf War, and homelessness, to name a few. They were not limited to visual or print media but also held demonstrations and speaking events, and included audio in some of their exhibitions. As the so-called "conscience of the art world," the Guerrilla Girls have continued to operate and take on diverse feminist issues with their trademark humor and reliance on statistics to answer the question of who bears the responsibility for representation—and to point to those who have failed in that responsibility, with the ultimate goal of inspiring lasting change.

Hayden Burt ’22

2020–21 McCrindle Intern